|

ExcFIG 5: Development of the excretory cell and the canals. A. The excretory cell is born at the end of gastrulation, ~270 minutes after first cell division at 22°C. At this stage, it has only a basal (outside) surface. B. At ~300-330 minutes, one or two vacuoles with apical surfaces (light gray) appear within the cell. At the same time, the cell starts to grow bilateral arms dorsolaterally. C. At 400-430 minutes of development, the apical surface expands and the tubular arms extend from the vacuoles into the canals. The bilateral canals have reached the lateral hypodermal ridges by now. The basal surface and the apical surface join at the junction of the duct cell. A thick electron-dense material (black line) accumulates in the lumen. D. Past the two-fold stage. On reaching the lateral hypodermis, the canals bifurcate extend anteriorly and posteriorly. Lumenal material disappears and is replaced by the terminal web within the cytoplasm surrounding the canal lumen (light gray lining). E. Post-hatching and adult stages. The excretory sinus and the canals are fully formed with numerous canaliculi originating from the central canal. The lumens of the canals assume a flattened shape. The terminal web persists around the apical surface.

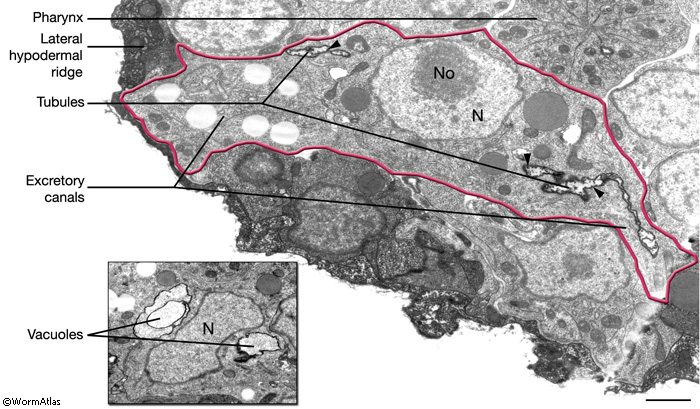

The newly born excretory cell is located on the ventral side of the developing pharynx of the embryo (ExcFIG 5A). Within an hour of its birth, one or two large vacuoles appear within the cell body (ExcFIG 5B and ExcFIG 6, inset). At about the same time, the cell starts to extend two processes dorsolaterally, and this bilateral canal extension is completed by the twofold stage (~450, minutes at 22°C) (ExcFIG 5C). The apical (lumenal) surface of the vacuole(s) is also enlarged as tubular arms grow from the initial vacuole(s) into the bilateral rudimentary canals (ExcFIG 6). A thick material that is visible by electron microscopy accumulates within the lumen (ExcFIG 6). At about the twofold stage, when they reach the lateral hypodermal ridges, the bilateral canals bifurcate to grow anterior and posterior arms located between the hypodermis and hypodermal basal lamina (ExcFIG5 D). The anterior arms run near the ventral margins of the lateral epidermal ridges, whereas the posterior arms run near the middle of them. By the time of hatching, posterior arms reach approximately the midbody, just past the V3 hypodermal seam cell. Between mid-three-fold stage and hatching, the electron-dense lumenal material disappears and an apical cytoskeletal material (terminal web) appears around the canals (Hedgecock et al., 1987; Buechner et al., 1999; Buechner, 2002; Berry et al., 2003). Simultaneously, the lumen of the canals assumes a flattened shape, and numerous canaliculi develop around the lumen to increase the apical surface area (ExcFIG 5E). The canals continue to grow actively during the first larval stage and reach their full length from the anterior tip of the organism to near the tip of the tail, just past the V6 seam cell by mid-L1. In the following three larval stages, canals grow passively with the growing length of the animal (Hedgecock et al., 1987; Buechner et al., 1999; Buechner, 2002; Berry et al., 2003). In the adult, the anterior segments of the canals are about 100 μm in length and 1 μm in diameter, whereas the posterior segments are about 1000 μm in length and 2 μm in diameter.

The two excretory canals run along the basolateral surface of the hypodermis on each side, in close association with the processes of CAN, PVD and ALA neurons along the posterior portions (ExcFIG 7A). Among these, CAN cells have been suggested to have a role in regulating the excretory canals (Hedgecock et al., 1987). The lateral subdomain of the outer circumference of the canals is closely linked to the hypodermis by an extensive system of large gap junctions and shares a common basal lamina with it (ExcFIG 7B&C) (see also Gap Junctions). The basal subdomain of the outer circumference of each canal remains in contact with the pseudocoelom over the full length of the canal (Nelson et al., 1983). Canals contain longitudinally oriented microtubules as well as mitochondria and Golgi bodies throughout their length, whereas endosomes are concentrated at the canal endings (ExcFIG 7B&C).

ExcFIG 7A: Excretory canals. A schematic of the cross section of the midbody showing excretory canals running on the right and left sides. Lateral nerve: CAN, PVD and ALA.

ExcFIG 7B&C: Excretory canal. B. Schematic rendering of a single canal located underneath the basal lamina of the hypodermis and in contact with the pseudocoelom on its basal surface. The canal makes extensive gap junctions to the surrounding hypodermis (thick black lines around the basal surface). The apical surface is surrounded by the terminal web (light gray line) on the cytoplasmic side and contains mucus (yellow line within lumen). Approximately 20 microtubules dot the cytoplasm. C. TEM of a cross section of a single excretory canal. The canal lumen is surrounded by numerous small channels called canaliculi (arrowheads). The terminal web is seen as electron-dense material surrounding the lumen. (M) Mitochondrion. Bar, 1 μm. (Image source: [Hall] N506C.)

ExcFIG 7D&E: Excretory canal. Model of the excretory canal in cross-section from an electron tomogram. D. Orthoslice through the tomogram. E. 3D model annotated from the tomogram. Canal is on the right, separated from nearby mesoderm (intestine or gonad) by the narrow space of the pseudocoelom. Colors here do not follow atlas code and have been chosen to mark sets of organelles by type. Red, ribosomes; green, lumen membrane and canaliculi that could be traced to luminal connections within a 400 nm interval along A/P axis (total depth of tomogram is 0.4 microns). Pale purple, white, pale yellow, blue mark other branched groups of canaliculi that must link to the lumen outside the reconstructed volume. (Purple) canal plasma membrane; (yellow) hypodermal cell plasma membrane; (brown) mitochondrion. (Arrows) indicate thin branched structures of unknown origin extending inside the excretory lumen. Note that the canaliculi are clustered close to the lumenal membrane, while ribosomes, mitochondria and other organelles are pushed to the exterior, away from the lumen of the canal (Ashleigh Bouchelion, Kristin Politi, KD Derr, William Rice and David Hall.)

The central lumen of each canal is narrower in the anterior compared with the posterior regions (Buechner, 2002). These lumena fuse and join with the origin of the excretory duct through a system of small channels termed the excretory sinus, just anterior to the cell’s nucleus (ExcFIG 8). The excretory sinus contains filamentous material that extends into the excretory duct.

ExcFIG 8: Secretory-excretory junction. Adherens junction (black arrowheads, bottom panel ) between the excretory cell, the gland cell, and the duct cell is shown by the schematic drawing overlaid on a TEM (middle panel ) of the region. The canals have joined to make the single excretory sinus within the excretory cell body (red). The osmotic fluid generated from the excretory cell passes through the sinus into the duct at this junction (top arrow, middle inset and bottom panel). The secretions of the gland cell pass through the convoluted secretory membrane (white arrowhead, bottom panel) to the duct (bottom arrows, middle inset and bottom panel). The secreted/ excreted material then travels to outside via the duct (curved brown arrow, middle panel). The collagenous cuticle lining of the duct continues throughout the duct. (Top right panel) Detail of the region from ExcFIG 1B. Bar, 1 μm. (TEM image source: [Hall] N510.)

In a fully formed excretory cell, a system of beaded canaliculi feed into the central lumen along the length of each canal (ExcFIG 7C). These canaliculi radiate from all sides of the lumen over short lengths to fill most of the canal cytoplasm (ExcFIG 7D&E). The shape of the central lumen can vary from a collapsed tube (~1 μm in breadth and 0.1 μm in depth) to a round cylinder (more than 1 μm in diameter when it is fluid-filled) (Buechner et al., 1999). The apical cytoskeleton surrounding the plasma membrane may reinforce the shape of the lumen to prevent it from deforming during fluid outflow (Buechner et al., 1999). The shapes of the canaliculi are more plastic, and under different conditions, the canaliculi may variably appear as smooth, narrow tubes or as a set of connected beads (50 nm beads connected by narrow necks); they can also break up into a set of larger (90 nm) vesicles that are disconnected from their neighbors and from the lumen. Recent studies using electron tomography to follow the adult canal in three dimensions show that the canaliculi are actually not beads on a linear “string”, but form short branched networks, with the stem of each branch attaching to the lumen (Zhang et al., 2012 and unpublished data) (ExcFIG 7D&E). Most canaliculi (beads) lie within 1-4 bead-length from their lumenal connection.

Both the central canal and canaliculi are lined by lumenal glycocalyx (mucin) that is essential for effective functioning of the secretory/excretory system (Jones and Baillie, 1995). A distinct set of mutations (“exc”: excretory canal defective) in genes expressed in the excretory cells is known to cause tubular pathologies in the form of gross cyst formation along the canal lumen, ranging from focal cysts, followed by normal-width segments, to large cysts involving almost the entire tubule (Buechner et al., 1999; Gao et al., 2001; Suzuki et al., 2001; Fujita et al., 2003). Some of these genes encode structural proteins such as SMA-1 (spectrin), necessary to reinforce the apical membrane on the cytoplasmic side, lumenal molecules such as mucin (LET-653) or ion channels (Jones and Baillie, 1995; McKeown et al., 1998; Berry et al., 2003).

Several proteins in the plasma membrane, lumenal membrane, or canaliculi have been implicated in the excretory canal cell’s important physiological role in osmoregulation, including an aquaporin (AQP-8), a chloride channel (CLH-3), several anion transporters (ABTS-2, SULP-4, SULP-5), a receptor-mediated cation export channel (GTL-2) and many vacuolar ATPases (VHA-1, 2, 4, 5, 8,11,12,13,15, 16 and VHA-17) (Liégeois et al., 2007; Hisamoto et al., 2008; Mah et al., 2007; Sherman et al., 2005; Teramoto et al., 2010; Hahn-Windgassen and Van Gilst, 2009).

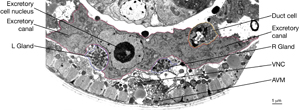

3 Excretory Gland Cell

The excretory gland is a binucleate, A-shaped cell that is formed by fusion of two identical (exc gl L and R) cells (ExcFIG 3C; ExcMOVIE 1) (Nelson et al., 1983). It has two separate cell bodies lying subventrally in the pseudocoelomic space, on the left and right sides and just posterior to the pharyngeal-intestinal valve (ExcFIG 4B). A large process from each cell body projects anteriorly along the dorsal surface of the ventral nerve cord and fuses with the other side at the level of the secretory-excretory junction, across the anterior edge of the excretory cell body (ExcFIG 8). The bilateral gland cell processes separate again anterior to this bridge region and fuse a second time near their anterior limit to form a ring-like process which projects into the nerve ring. The gland cell is suggested to receive synaptic input from nerve ring neurons in this region (Nelson et al., 1983).

ExcMOVIE 1: A. DIC image of left excretory gland (Exc. gland). Amsh: amphid sheath cell. Left lateral view. B. 3-D reconstruction of excretory gland cells. 3-D movie was created from confocal images of a strain expressing the GFP marker linked to the promoter for B0403.4 [dpy-5(e907) X;sIs 13607 (rCes B0403.4::GFP + pCeh361)], using Zeiss LSM 5 Pascal software v. 3.2. (Image source: R. Newbury and D. Moerman.) Click on image to play movie.

The gland cell cytoplasm contains an extensive network of dilated cisternae of rough endoplasmic reticulum, many mitochondria and ribosomes, Golgi complexes, and clusters of electron dense secretory granules (Nelson et al., 1983). These granules are concentrated around the cytoplasmic bridge region near the secretory membrane, which is a specialized portion of the cell membrane that connects to the origin of the excretory duct (ExcFIG 8). Any glandular secretions entering the duct may conceivably reach the excretory sinus through the secretory-excretory junction. As the animal grows the gland cell enlarges in proportion to the size of the animal, and the number of secretory granules increases, although the changes are not synchronous with the molting cycle (Nelson et al., 1983). The vesicles become less electron-dense in the adult gland. In dauer larvae, the gland cell cytoplasm contains only a loose membraneous network and no secretory granules. This does not seem to be a result of starvation but rather is related to this developmental state itself. The function of excretory gland cell is currently unknown. It does not seem to be involved in molting in C. elegans (Singh and Sulston, 1978), and ablation of the gland cell does not result in any obvious defects (Nelson and Riddle, 1984).

4 Duct Cell

The excretory duct of C. elegans is a 15 μm long, cuticle-lined channel that connects the excretory system to outside via the excretory pore located at midline on the ventral side of the body. The duct cell surrounds the duct from its origin to the boundary of the pore cell, covering about two thirds (9-10 μm) of the duct, which follows a looped path within the cell (ExcFIG 1A&B). The duct cell is located just anterior and lateral (left or right) to the excretory cell body, and hence, the initial portion of the duct can be located either to the right or the left of the excretory cell (Nelson et al., 1983). The morphology of the duct cell, as well as the placement of the duct and pore along the anterior-posterior axis within related Caenorhabditis species seems to be determined by the zinc-finger gene lin-48 (Wang and Chamberlin, 2002; 2004).

Inside the duct cell, the plasma membrane surrounding the duct invaginates extensively, creating lamellar stacks which greatly increase the surface area of the membrane (ExcFIG 4A and ExcFIG 9C). These lamellar sheets become more elaborate as the animal matures and are similar to those seen in hypodermis (White, 1988). Laser ablation of the duct cell leads to absence of cuticle within the duct cell portion of the excretory duct after a molt, suggesting duct cell integrity is required for formation of cuticle lining within the duct cell environment (Nelson and Riddle, 1984).

Mutations that slow the growth of the duct cell lumen during embryogenesis can lead to rod-like lethality if the lumen breaks down anywhere along the length of the duct (Stone et al., 2009). In addition, as with the excretory cell, duct cell ablation eventually causes fluid accumulation within the animal followed by death, suggesting a function in osmotic/ionic regulation. This function is also supported by the finding that In other nematode species the pulse rate of the duct changes according to the osmolarity of the environment. However, in C. elegans, the only stage when any duct pulsation is observed is the dauer larva (See Dauer Cuticle) (Nelson and Riddle, 1984).

ExcFIG 9: The excretory pore cell and the duct cell. A. TEM of horizontal section. Ultrastructure of the excretory pore and its cuticle. (Image source: [Hall] N533 N1 C629B.) B. TEM, transverse section showing the excretory pore that splits the ventral nerve cord into two at midline. The pore cell makes adherens junctions (arrowheads) to hypodermis on the ventral side and the pore cuticle becomes continuous with the body cuticle. Bar, 1 μm. (Image source: [Hall] N513A.) C. TEM of transverse section. The excretory duct cell contains numerous lamellae (Lm) that increase the apical surface. The duct shows a tortuous path within the cell. Arrowheads point to regions in which the pore cell makes intracellular adherens junctions. (N), Duct cell nucleus. Image source: Hall.)

D. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) image of an adult C. elegans showing the pore located at the ventral midline and at the same level as the anterior deirid sensillum. The excretory pore is open in all stages of the animal including the dauer. (Image source: [Hall] SEM archive.)

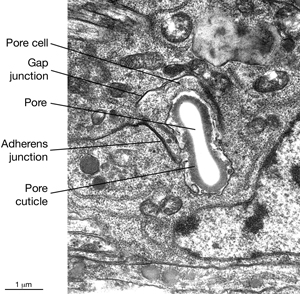

5 Pore (excretory socket) Cell

Like the duct cell, the pore cell is a specialized, transitional, epithelial cell. It encloses the ventral third of the duct and forms an adherens junctions with the duct cell at the duct cell-pore cell junction. It also makes junctions with itself by wrapping around the duct (Nelson et al., 1983). The pore cell underlies the excretory pore on the ventral side of the animal where the duct wall cuticle becomes continuous with the body wall cuticle (ExcFIG 9A). Around this region, the pore cell makes adherens junctions to the surrounding hypodermis and seals the pore (ExcFIG 9B). In the embryo, the G1 cell acts as the excretory pore cell (excretory socket cell). After hatching, G1 becomes a neuroblast and the pore function is taken over by G2 (ExcFIG 10). Eventually at L2 stage, G2 divides and the posterior daughter of G2 (G2.p) becomes the mature excretory pore cell, while the anterior daughter (G2.a) becomes a neuroblast (Nelson et al., 1983, Sulston, 1983). Mutations that inhibit this pore cell swap, or inhibit the remodeling of adherens junctions between the duct cell and the new pore cell can cause rod-like lethality if the duct/pore junction is lost (Abdus-Saboor et al., 2011; Mancuso et al., 2012).

The duct cell and pore cell share responsibility for secreting the new duct cuticle at each molt. In animals where the pore cell is ablated, cuticle is completely absent throughout the duct (Nelson and Riddle, 1984). The excretory pore remains open throughout all developmental stages including the dauer larva (See Dauer Cuticle).

ExcFIG 10: The G1 and G2 cell in the L1 larval stage.

6 List of Cells of the Excretory System

Excretory canal cell (exc cell)

Excretory gland cell (syncytial)

Exc gl L

Exc gl R

Excretory duct cell

Excretory pore cell:

G1 (only at embryo stage)

G2 (only at L1 stage)

Exc pore cell [aka excretory socket cell] (L2 and later stages)

More figures of the excretory system

7 References

Abdus-Saboor, I., Mancuso, V., Palozola, K., Murray, J., Howell, K., Huang, K., Norris, C.R., Hall, D.H. and Sundaram, M.V. (2011) Notch and Ras promote sequential steps of excretory (renal) tubulogenesis. Development 138: 3545-55. Article

Berry, K.L., Buelow, H.E., Hall, D.H. and Hobert, O. 2003. A C. elegans CLIC-like protein required for intracellular tube formation and maintenance. Science 302: 2134-2137. Abstract

Buechner, M., Hall, D.H., Bhatt, H. and Hedgecock, E.M. 1999. Cystic canal mutants in Caenorhabditis elegans are defective in the apical membrane domain of the renal (excretory cell). Dev. Biol. 214: 227-241. Article

Buechner M. 2002. Tubes and the single C. elegans excretory cell. Trends Cell Biol. 12: 479-484. Abstract

Chitwood, B. G. and Chitwood, M. B. 1950. General structure of nematodes. In An introduction to nematology. Chapter 2. pp 7-27. Baltimore, University Park Press.

Davey, K.G. and Kan, S.P. 1968. Molting in a parasitic nematode, Phocanema decipiens. IV. Ecdysis and its control. Can. J Zool. 46: 893-898. Abstract

Fujita, M., Hawkinson, D., King, K.V., Hall, D.H., Sakamoto, H. and Buechner, M. 2003. The role of the ELAV homologue EXC-7 in the development of the Caenorhabditis elegans excretory canals. Dev. Biol. 256: 290-301. Article

Gao, J., Estrada, L., Cho, S., Ellis, R.E. and Gorski, J.L. 2001. The Caenorhabditis elegans homolog of FGD1, the human Cdc42 GEF gene responsible for faciogenital dysplasia, is critical for excretory cell morphogenesis. Hum. Mol. Gen. 10: 3049-3062. Article

Hahn-Windgassen, A. and Van Gilst, M.R. 2009. The Caenorhabditis elegans HNF4alpha Homolog, NHR-31, mediates excretory tube growth and function through coordinate regulation of the vacuolar ATPase. PLoS Genet. 5: e1000553. Article

Hedgecock, E., Culotti, J.G., Hall, D.H. and Stern, B.D. 1987. Genetics of cell and axon migrations in Caenorhabditis elegans. Development 100: 365-382. Article

Hisamoto, N., Moriguchi, T., Urushiyama, S., Mitani, S., Shibuya, H. and Matsumoto, K. 2008. Caenorhabditis elegans WNK-STE20 pathway regulates tube formation by modulating ClC channel activity. EMBO Rep. 9: 70-5. Article

Jones, S.J., and Baillie, D.L. 1995. Characterization of the let-653 gene in Caenorhabditis elegans. Mol. Gen. Genet. 248: 719-726. Abstract

Liégeois S, Benedetto A, Michaux G, Belliard G, and Labouesse M. 2007 Genes required for osmoregulation and apical secretion in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics 175: 709-24. Article

Mah, A.K., Armstrong, K.R., Chew, D.S., Chu, J.S., Tu, D.K., Johnsen, R.C., Chen, N., Chamberlin, H.M. and Baillie, D.L. 2007. Transcriptional regulation of AQP-8 , a Caenorhabditis elegans aquaporin exclusively expressed in the excretory system, by the POU homeobox transcription factor CEH-6. J. Biol. Chem. 282: 28074-86. Article

Mancuso, V.P., Parry, J.M., Storer, L., Poggioli, C., Nguyen, K.C.Q., Hall, D.H. and Sundaram, M.V. 2012. Components of the apical extracellular matrix are required to maintain epithelial junction integrity in C. elegans. Development 139: 979-90. Abstract

McKeown, C., Praitis, V., and Austin, J. 1998. sma-1 encodes a bH-spectrin homolog required for Caenorhabditis elegans morphogenesis. Development 125: 2087-2098. Article

Nelson, F.K. and Riddle, D.L. 1984. Functional study of the Caenorhabditis elegans secretory-excretory system using laser microsurgery. J. Exp. Zool. 231: 45-56. Abstract

Nelson, F.K., Albert, P.S. and Riddle, D.L. 1983. Fine structure of the Caenorhabditis elegans secretory-excretory system. J. Ultrastruct. Res. 82: 156-171. Article

Sherman, T., Chernova, M.N., Clark, J.S., Jiang, L., Alper, S.L. and Nehrke, K. 2005. The abts and sulp families of anion transporters from Caenorhabditis elegans. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 289: C341-51. Article

Singh, S.S. and Sulston, J.E. 1978. Some observations of moulting in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nematologica 24: 63-71. Abstract

Stone, C.E., Hall, D.H. and Sundaram, M.V. 2009. Lipocalin signaling controls unicellular tube development in Caenorhabditis elegans. Developmental Biol. 329: 201-211. Article

Sulston, J.E., Schierenberg, E., White, J.G. and Thomson, J.N. 1983. The embryonic cell lineage of the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Dev. Biol. 100: 64-119. Article

Suzuki, N., Buechner, M., Nishiwaki, K., Hall, D.H., Nakanishi, H., Takai, Y., Hisamoto, N. and Matsumoto, K. 2001. A putative GDP-GTP exchange factor is required for development of the excretory cell in Caenorhabditis elegans. EMBO Rep. 21: 530-535. Article

Teramoto, T., Sternick, L.A., Kage-Nakadai, E., Sajjadi, S., Siembida, J., Mitani, S., Iwasaki, K. and Lambie, E.J. 2010. Magnesium excretion in I requires the activity of the GTL-2 TRPM channel. PLoS One 5: e9589. Article

Wang, X. and Chamberlin, H.M. 2002. Multiple regulatory changes contribute to the evolution of the Caenorhabditis lin-48 ovo gene. Genes Dev. 16: 2345-2349. Article

Wang, X. and Chamberlin, H.M. 2004. Evolutionary innovation of the excretory system in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nat. Genet. 36: 231-232. Article

White J. 1988. The Anatomy. In The nematode C. elegans (ed. W. B. Wood). Chapter 4. pp 81-122. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, New York. Abstract

Zhang, H., Kim, A., Abraham, N., Khan, L.A., Hall, D.H., Fleming, J.T. and Gobel, V. 2012. Clathrin and AP-1 regulate apical polarity and lumen formation during C. elegans tubulogenesis. Development 139: 2071-2083. Article |